Saint Francis of Assisi – a saint for all seasons

Saint Francis of Assisi is the inspiration behind San Damiano Corporation Ltd, which trades as SD Care Agency. The name San Damiano is taken from the chapel in Assisi, Umbria where St Francis received his call from God that led to the formation of the Franciscan Order and philosophy.

Francis Mirandah, Founder & CEO

Caravaggio’s ‘remarkable’ Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, c1595.

© Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

St Francis has inspired many artists (he himself contemplated God through art) and is a recurrent protagonist in the National Gallery’s collection, which is holding a free exhibition until the end of July. A description in the National Gallery’s website is reproduced here.

Ground Floor Galleries

Come face-to-face with one of history’s most inspirational and revered figures in the first major UK art exhibition to explore Saint Francis of Assisi’s life and legacy.

Presenting the art and imagery of Saint Francis (1182–1226) from the 13th century to today, this exhibition looks at why this saint is a figure of enormous relevance to our time due to his spiritual radicalism, commitment to the poor, and love of God and nature, as well as his powerful appeals for peace, and openness to dialogue with other religions.

From some of the earliest medieval panels, relics and manuscripts to modern-day films and a Marvel comic, the exhibition shines a light on how Saint Francis has captured the imagination of artists through the centuries, and how his appeal has transcended generations, continents and different religious traditions.

This exhibition is curated by Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery and Joost Joustra, the Ahmanson Research Associate Curator in Art and Religion at the National Gallery.

Saint Francis of Assisi review – a saint for all seasons

Francis is also a saint for all seasons: a pioneer for Renaissance artists, a mystic for baroque visionaries, a muse for the Romantics, a social radical for our times. He stands for peace, hope and love, for equality, hugging and ecology. The present pope took his name. He is such an inspiration to artists (he himself contemplated God through art) as to be almost a recurrent protagonist in the National Gallery’s own collection, and more images have arrived from abroad to tell the life, and imagine the man, in this enthralling and magnificent show.

‘Renaissance Francis, struggling out of his costly coat to press it on a poor man’: Saint Francis and the Poor Knight,

and Francis’s Vision, 1437-44 by Sassetta. © The National Gallery, London

Saint Francis Before the Sultan by Fra Angelico, 1429.

Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany/ Bernd Sinterhauf

Most remarkable of all, perhaps, is the Caravaggio on loan from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Connecticut, showing the saint receiving the stigmata at the mountain shrine of La Verna in Arezzo. Francis falls back into the arms of an angel, eyes open yet sightless with astonishment. Moonwrack shoots across the night sky and in the darkness his followers sleep, missing the moment altogether.

And this is one of the show’s marvellous achievements. In directing your eye to all these images of a single man, and his life, it alters your perceptions of both the man and the painters. Francis struggling with his coat is the first of a narrative sequence by the 15th-century Sienese artist Sassetta, all displayed in a central gallery to which you return. Sassetta’s humorous expressiveness astounds. Here is Francis’s furious silk merchant father, disgusted to see these expensive clothes rejected, and his son’s “Sorry, Dad” face. Here are the crimson-clad cardinals in Rome, rolling their eyes and sighing as the sackcloth Francis shows up to receive nothing less than a blessing and even the permission of the pope to start a whole new order.

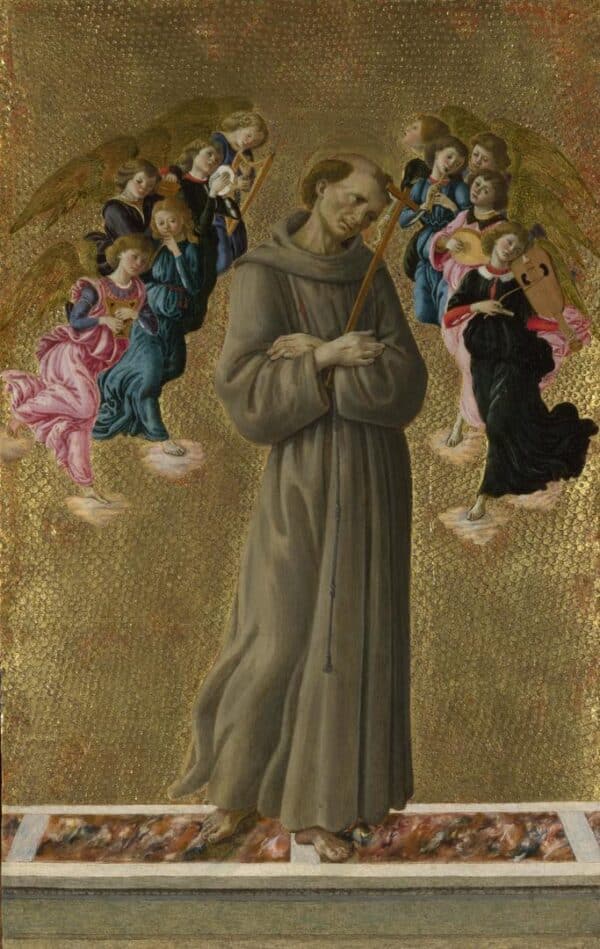

Saint Francis of Assisi with Angels

Sandro Botticelli © The National Gallery, London

Nothing brings you quite so close to Francis as this show. It has his beautifully simple letters, his songs, hymns and prayers in manuscript copies, even his own drawing, in which a cross rises out of a head with a bristly Desperate Dan chin. It has his bell and his books, and even, at the very end, a faded brown habit with a discoloured rope that Francis is believed to have worn.

And right beside these is one of the Umbrian artist Alberto Burri’s celebrated Sacchi (sacks), from 1953, a canvas stitched out of patches of rough sacking with occasional holes, one of which is here filled with blood-red paint. Irresistibly recalling the nail holes Francis received as stigmata, it also evokes the sackcloth habit in its nearby reliquary and the darned cloth depicted in so many paintings, right back to the poor man’s rags by Sassetta.

And so it goes with this show. It feels mobile, animate, a living exhibition. You see Zurbarán’s Francis again at the end, the cowl now falling back as he talks intensively to God. You see Renaissance stigmata coming down from heaven reprised as blood-red lasers in a fabulous Marvel comic. There are film clips from Franco Zeffirelli, Federico Fellini, Pier Paolo Pasolini. The verdant living wall outside speaks to the art within; the beauty and profundity of it all so superbly presented by the National Gallery’s own director, Gabriele Finaldi, curating with his colleague Joost Joustra.

I can think of no other show that has been blessed by the pope. And this one deserves it, from first to last. It follows Francis of Assisi in spirit too – being open, for free, to all.